Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease, characterized by the presence or growth of endometrium-like tissue outside the uterus. It affects approximately 10% of women in their reproductive age, impacting around 190 million women worldwide [1,2]. Endometriosis is predominantly present in the pelvis and can be subdivided into three subtypes: superficial endometriosis (involving the peritoneal surface), ovarian endometriosis (including endometriotic cysts or endometrioma), and deep endometriosis (infiltrating the peritoneal surface and invading, among others, the bowel, ureter, bladder, and vagina). Endometriosis can also occur outside of the pelvis, i.e., extra-pelvic endometriosis, including the perineum, abdominal wall, and thorax [1–3].

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) is a rare form of endometriosis in which ectopic endometrial-like tissue is present in the subcutaneous adipose layer, fascia, or the muscles of the abdominal wall [3,4]. The overall prevalence of AWE ranges from 0.03% to 3.5%. Unfortunately, due to the lack of consistent epidemiological and histological data, it is difficult to determine the true incidence of AWE [5–9].

AWE can occur spontaneously in the abdominal wall through vascular or lymphatic spread of endometriosis from the abdominal cavity and/or through metaplastic transformation. Alternatively, it may occur as a result of iatrogenic implantation of endometrium or endometriotic tissue in a surgical scar after abdominal-pelvic surgery [5,10]. Therefore, previous surgical procedures, including cesarean section, laparoscopy, or hysterectomy, are risk factors for AWE [2,3,7,11]. The most common location for incisional AWE is in a cesarean scar. As the number of cesarean sections is increasing worldwide, it is expected that the occurrence of AWE will also rise [5].

Women with AWE report complaints such as localized abdominal tenderness, chronic pain, or pain occurring either during or prior to menstruation. In addition, skin alterations, local swelling, bruising, or bleeding of the infiltrated area may occur [4]. The differential diagnosis includes hernias, lipomas, sebaceous cysts, as well as malignant tumors [10]. Malignant degeneration of AWE has been reported; however, it occurs rarely [12].

There are different treatment options for women with symptomatic AWE. The primary treatment is surgical removal of the nodule [4]. However, recurrence rates range from 4.5% to 9% [10,13–16]. Hormonal medications and pain relief options may be considered if patients experience mild symptoms or do not opt for surgical intervention [7,17]. Unfortunately, due to the limited and low-quality data on treatment of AWE, it is still uncertain what the optimal approach is for patients with this condition [2]. Therefore, there is a need for more comprehensive research on AWE. The aim of this cohort study is to investigate treatment satisfaction and recurrence of AWE after receiving treatment in a tertiary referral center for endometriosis.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Endometriosis Center of the Amsterdam University Medical Center (AUMC) in the Netherlands. The study was approved by the medical ethical review committee of the AUMC under number 2021.0702.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were diagnosed with AWE by imaging (ultrasound and/or MRI) or biopsy during a period of ten years (2009–2018). To be included, patients had to have received the AWE diagnosis at least one year prior to the start of this study to ensure sufficient follow-up to observe recurrence after treatment. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years of age, had been diagnosed with inguinal endometriosis, or were unable to speak or read English or Dutch.

To identify patients with AWE, we conducted a search using CTcue within the EPIC Electronic Patient Database. CTcue (version 2.1, CDC; CTcue B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) is a healthcare data platform that enables healthcare professionals to access, search, and analyze clinical data efficiently within electronic patient records. Using this software, we searched the EPIC system with the following terms: “abdominal wall endometriosis”, “scar endometriosis”, “cesarean section endometriosis”, “rectus abdominus endometriosis”, “belly button endometriosis”, “fascia endometriosis”, “cutaneous endometriosis”, and “skin endometriosis”. The search terms were applied in both Dutch and English, including variant spellings. If a term appeared anywhere in a patient’s electronic file, it was flagged as a hit.

Eligible patients were contacted to participate in the survey and signed an informed consent form. A QR code and a link to the questionnaire were sent by email and/or on paper by mail. The program Forms (version 2024, Microsoft Corporation) was used to store questionnaire data.

In addition, data were collected from electronic patient records, including demographics, medical history, clinical presentation, age at time of symptoms/diagnosis of AWE, previous surgical/gynecological operations, diagnostic imaging methods, nodule size and location within the abdominal wall, histology, type of treatments, side effects of treatment, and treatment satisfaction. Recurrence was defined as re-confirmation of the condition at the same abdominal wall location via imaging (MRI or ultrasound). If followed by surgical excision, diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological examination. The study outcomes were recurrence rate of AWE after surgical treatment and patient satisfaction.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics version 28.0.1. Nominal and ordinal variables were analyzed with either the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test, while continuous variables were analyzed using either the independent-sample T-test or the Mann–Whitney U test. The outcome measure was the odds of AWE recurrence after surgical removal, or after combined hormonal treatment and surgery. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

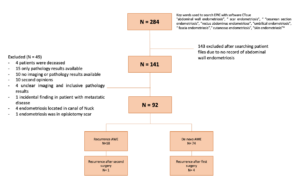

Two hundred and eighty-four patients were extracted from the electronic patient record system. After reviewing records, 143 patients were excluded due to the absence of AWE, and 49 cases were excluded for various other reasons (see flow chart). Ultimately, 92 patients (mean age 33.7 years, SD 6.1) were eligible for inclusion. The median follow-up duration was 9 months. Among them, 74 patients had de novo AWE, and 18 were referred for treatment of AWE recurrence after previous surgery in another hospital.

Seventy-one patients (77.2%) had a prior cesarean section, four (4.3%) had only undergone abdominal surgery (e.g., bladder, intestines, or appendix), and five (5.4%) had only undergone gynecological surgery (e.g., ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus). Twenty-nine patients (31.5%) had a known diagnosis of deep endometriosis prior to AWE diagnosis, and 13 patients (14.1%) had a history of adenomyosis. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameters | Total n=92 |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 33.7 ± 6.1 |

| Length (cm) | 169.3 ± 13.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.0 ± 19.0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.5 ± 6.3 |

| Prior caesarean section | 71 (77.2%) |

| Prior abdominal surgery1 Only prior abdominal surgery |

17 (18.5%) 4 (4.3%) |

| Prior gynaecological operation 2 Only prior gynaecological surgery3 |

14 (15.2%) 5 (5.4%) |

| Prior history of endometriosis3,4 Deep endometriosis Adenomyosis |

36 (39.1%) 29 (31.5%) 13 (14.1%) |

Normal data are presented as mean ± standard deviations, non-normal data as median [interquartile range] and dichotomous data are expressed as frequencies n (%).

1 Prior abdominal surgery includes i.e. the intestines, appendix and bladder; 2 Prior gynecological operations included all those that involved the ovaries, uterus and fallopian tubes; 3Only prior gynecological surgery included (ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes); Table does not present patients with prior caesarean section and/or prior other abdominal surgery; 4 Includes patients that have previously been surgically treated for deep endometriosis or patients with radiologically confirmed deep endometriosis /adenomyosis.

First symptoms

At first presentation, patients reported various symptoms (Table 2), with most experiencing more than one. The most common symptom was localized pain, including cyclic and chronic pain, often accompanied by a palpable abdominal wall mass. Three patients (3.6%) were asymptomatic, with AWE found incidentally.

| Parameters | Total n=92 |

|---|---|

| Localized pain | 53 (63.1%) |

| General abdominal pain¹ | 31 (36.9%) |

| Palpable mass | 34 (40.5%) |

| Colouring skin | 3 (3.6%) |

| Bleeding from the AWE site | 6 (7.1%) |

| No symptoms | 3 (3.6%) |

Data are presented as frequencies n (%).

1 General pain was defined as chronic and cyclic pain in the abdomen, not indicated in specific site

Radiological findings at first presentation

Sixty-seven patients (74.4%) underwent MRI, and 73 (80.2%) underwent ultrasound. Only four patients (4.5%) had abdominal CT, most often for unexplained abdominal pain or unrelated reasons (e.g., inguinal hernia). MRI reports indicated that 58 patients (63.7%) had AWE in a surgical scar (subcutaneous adipose layer and fascia), 15 patients (16.5%) had AWE in the deep abdominal muscle, and 13 patients (14.3%) had umbilical AWE. The average lesion size on imaging was 2 cm (IQR 4.2 cm). The mean time to diagnosis was 2.3 years (range 0.5–5 years).

Treatment

Most patients (76%) underwent surgery. Treatments were often combined (Table 3): 33.7% had both hormonal therapy and surgery, 5.4% had surgery with painkillers only, and 14.1% received all three treatments. Twenty-one patients (22.8%) had surgery only, while four patients (4.3%) received hormonal treatment only.

Of the 18 patients referred with AWE recurrence, 12 had a second surgery at AUMC. Post-excision pathology showed an average lesion size of 4.3 cm (IQR 2.8 cm) with tissue margins ≥ 10 mm; all margins were negative for endometriosis. Not all patients with concomitant pelvic endometriosis underwent complete surgical treatment. Only one of five patients reported using painkillers, including opioids or NSAIDs.

| Patientswith survey n=41 | Total n=92 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonaltreatment | 25 (61.0%) | 48 (52.7%) |

| Surgery First surgical treatment at AUMC Second surgery, but first in our center |

34 (82.9%) - - |

70 (76.0%) 52 (56.4%) 12 (66.0%) |

| Surgicaltreatment combinations Surgery and hormonal medication Surgery and painkillers Surgery, painkillers and hormonalmedication Only surgery |

7 (16.7%) 1 (2.4%) 13 (31.0%) 13 (31.0%) |

31 (33.7%) 5 (5.4%) 13 (14.1%) 21 (22.8%) |

| Pain-management | 17 (41.4%) | 18 (19.6%) |

Data are presented as frequencies n (%).

Recurrence

Among the 52 patients primarily treated at AUMC, four (8%) experienced recurrence: three had combined hormonal therapy and surgery, and one had surgery only. In the referral group, 12 patients underwent a second surgery, with one patient (8%) experiencing a second recurrence.

Treatment satisfaction

Forty-one of 92 patients (44.5%) responded to the questionnaire, rating their experience with hormonal and surgical treatments on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). Median scores were 5.0 (IQR 4.0) for hormonal therapy and 7.5 (IQR 4.0) for surgical treatment. Reported side effects of hormonal therapy included mood swings, hot flashes, and headaches; other complaints were weight gain, concentration problems, forgetfulness, and lowered libido. The difference between satisfaction scores was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) is a rare form of endometriosis, with ectopic endometrial-like tissue present in the subcutaneous adipose layer or abdominal wall muscles. In this study, we investigated patient satisfaction and recurrence of AWE over a median follow-up of 9 months in a tertiary referral center. The cohort included both de novo AWE cases and recurrences after prior excision elsewhere. Following surgical treatment at our center, the recurrence rate was 8% in both groups. Patients reported higher satisfaction with surgery compared to hormonal treatment, although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Most patients had a history of prior pelvic surgery, supporting the hypothesis that AWE is predominantly iatrogenic, caused by transfer of endometrial or endometriotic cells to the abdominal wall [9]. In our cohort, 31.5% had a history or subsequent diagnosis of deep endometriosis—higher than the 13% reported in one of the largest AWE cohorts, and roughly three times the overall incidence in the general population [10]. Being a referral center likely explains this high rate of concomitant pelvic endometriosis.

The most common presentation in this study was localized pain, both cyclic and chronic, often with a palpable abdominal wall mass. Because AWE symptoms are non-specific and slowly progressive, diagnosis is frequently delayed. Previous studies reported up to 3.6 years from initial surgery to diagnosis [5,18]; in our cohort, symptom onset occurred within one year of index surgery, with mean time to diagnosis of 2.3 years (range 0.5–5).

Ultrasound is typically the first imaging modality for AWE and was used in 80.2% of patients. Typical findings include hypoechoic nodules with spiculated margins, though appearance can vary with menstrual phase, bleeding, and inflammation [19]. Incisional AWE was the most frequent type, consistent with prior reports [20,21]. MRI was performed in most patients to confirm diagnosis, showing small T1 hyperintense foci within T2 hypointense nodules.

In our population, additional findings were observed on MRI. Thirty-one and a half percent of patients had deep endometriosis, and 17% had adenomyosis. It is common for different types of endometriosis to coexist. Gonzales et al. [22] demonstrated a significant association between adenomyosis and deep endometriosis. Piriyev et al. [21] reported that 32.5% of their AWE cases had additional adenomyosis, and that deep endometriosis involved 7.5% of rectal, 2.5% of bladder, 6.2% of intestinal, and 22.5% of uterosacral tissue, which aligns with our findings.

It is currently recommended to perform a complete excision, if possible, or otherwise apply long-term medical treatment when managing AWE [4]. In our cohort, most patients underwent surgery. Surgical treatment offers the best opportunity for both definitive diagnosis and therapy. We performed excision with a margin of at least 5–10 mm of surrounding tissue to decrease the risk of recurrence. To date, our study is the only one that has addressed the surgical margin of the wound as a measure to lower AWE recurrence rates. Although all examined tissue margins were disease-free, a recurrence rate of 8% was found. This may be related to endometriotic cells or microscopic foci remaining near the resection site. Over time, these residual cells can proliferate and lead to recurrence. Alternatively, although speculative, lymphovascular dissemination and/or metaplasia could also explain these recurrences, as they all occurred in patients with negative tissue margins at primary excision.

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, it is one of the larger cohort studies on AWE with an extended follow-up period to track recurrences [23-26]. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study to include patient satisfaction rates regarding their treatment, providing valuable insight into patients’ experiences.

However, our study also has several limitations. First, the retrospective design may introduce recall bias, especially since many patients received their treatment several years before the study. Ideally, a prospective cohort study would better assess treatment effects and patient satisfaction. Additionally, because only patients with a minimum follow-up period of nine months were included, long-term recurrence rates and treatment effectiveness remain uncertain.

This study was conducted at a tertiary referral center, which may include more severe cases of endometriosis than those typically seen in the general population. It represents a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent standard treatments, many of whom were treated before alternative modalities, such as high-intensity focused ultrasound or cryoablation, became available. Therefore, none of the patients in our cohort were offered these treatments. Some may have been referred back to other hospitals after treatment, potentially leading to missing data on symptoms or recurrences.

Lastly, the response rate to our online questionnaire may have introduced selection bias, potentially skewing patient satisfaction results. The response rate in our study was 43%, which can be considered a limitation. Yet, according to the literature, the average response rate for online questionnaires is 44%, making our results comparable.

Emerging therapies such as cryoablation, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), and sclerotherapy hold promise for the treatment of AWE and should be further evaluated as alternatives to surgery. Future studies incorporating these ablation therapies are needed to assess their effectiveness and patient satisfaction, preferably including a cost-effectiveness analysis of all available treatment options.

Hormonal treatment remains beneficial for patients who opt against surgery or as postoperative management to reduce recurrence risk, especially in those with a history of pelvic endometriosis. In addition, hormonal therapy may be an option for patients with large-volume AWE to reduce lesion size prior to surgery.

Conclusion

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) is a rare subtype of endometriosis. Patients report greater satisfaction with surgical treatment compared to medical therapy, with a recurrence rate of 8% following surgery. This may be related to the high proportion of patients with pelvic endometriosis, in which recurrences may not result from residual tissue but rather from pelvic dissemination or metaplasia.