Introduction

The mammalian ovulatory cycle requires an elegant interplay between several hormones, including sequences leading to the gonadotropin surge, triggering oocyte maturation and ovulation [1]. Ovulation has been attributed primarily to luteinizing hormone (LH) activity, while follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) has been shown to be responsible for follicular growth and development, and other peri-ovulatory events including increasing LH receptor expression [2]. FSH is capable of inducing ovulation in the absence of LH [3], implying that its role in cycle dynamics remains to be fully elucidated.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist analogs are commonly used during IVF cycles to diminish mid-cycle endogenous LH and FSH production, thereby preventing premature ovulation. In such a protocol, the last FSH dose is often administered at least 24 hours prior to the ovulation trigger. Given the relatively short half-life of FSH, serum FSH levels may drop in the many hours preceding the time of ovulation, which physiologically differs from the natural surge of FSH just prior to ovulation [4].

Considering the role that FSH plays in peri-ovulation follicle development and oocyte maturity [2,3], it is important to study what effect, if any, this peri-ovulatory decline in FSH has on the outcomes of IVF cycles. The clinical importance of this question is further emphasized by research showing a positive association between follicular FSH levels and IVF outcomes [5]. It is therefore vital to better understand the role that FSH plays in this process, and the clinical effects of its manipulation.

To address these questions, we sought to use our own clinical experiences to clarify the relationship between giving IVF patients additional FSH at the time of ovulation trigger (boost) and the number of retrieved oocytes, number of mature oocytes, number of blastocysts and number of euploid embryos formed.

Materials and methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted of patients who underwent IVF or embryo banking cycles with preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) at the NYU Langone Fertility Center from January 2015 through December 2018. Recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin was used for ovulation triggering, and patients with GnRH agonist triggers were excluded. Sperm parameters dictated the use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Cycles were separated into two groups for comparison: those who received only trigger injections on the trigger day (No Boost), and those who also received additional FSH (Boost). The decision to administer a boost was made by the supervising physician and based on a plateau or decrease of the trigger-day estradiol level. GnRH suppression regimens included Antagon or Cetrotide. Patients undergoing oocyte freeze cycles, cycles without PGS testing, or cycles that were cancelled prior to retrieval were excluded.

Preliminary analysis of our data revealed that hyper-responders were less likely to have received a boost and boost patients had markedly and statistically significant lower trigger-day estrogen levels (E2trig). Across all the months that were compared, the mean E2trig ranged from 1327 to 2035 pg/ml for Boost group versus 2052 to 2722 pg/ml for No Boost group, p < 0.05. Because we wanted to determine the effects of a boost within similar patient cohorts, we assembled comparison groups with comparable estrogen responses by stratifying Boost and No Boost patients by age and E2trig levels, and then randomly matching Boost and No Boost patients from the same age groups and E2trig strata.

The Boost and No Boost groups’ trigger-day estrogen levels (E2trig) were randomly matched as follows. Patients in the Boost pool were separated by Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) age group. Each SART age group was then further segregated into quartiles based on their trigger-day estrogen level mean value, and the mean +/- 1.5 standard deviation’s (SD’s). Patients in the No Boost pool were similarly divided by SART age groups and then further separated into 4 groups by using the Boost E2trig mean and moving 1.5 SD’s in each direction in the No Boost population. Hyper-responding patients in the No Boost population with E2trig values that were greater than the Boost group’s maximum E2trig value were excluded from the No Boost pool, so as to create clinically similar populations with E2trig values in the No Boost pool that are analogous to those in the Boost pool. Patients from the No Boost pool were then randomly selected from each of the corresponding 4 quartiles and added to form a group of No Boost patients that correspond in a 1:1 match for each of the 4 Boost quartiles: A: E2trig < (mean – 1.5 SD); B: (mean – 1.5 SD) < E2trig < mean; C: mean < E2trig < (mean + 1.5 SD); D. E2trig > (mean + 1.5 SD).

962 patients were included in this final matched comparison. 481 patients who received a boost, and 481 who did not. Each group was further sub-divided by SART age groups. Ages ranged from 24 through 47 years old. Demographics, days of gonadotropin, number of retrieved oocytes, number of mature oocytes, fertilization rates, number of blastocysts, and number of euploid embryos, were compared using Student’s t-test or X2 on Microsoft Excel.

Results

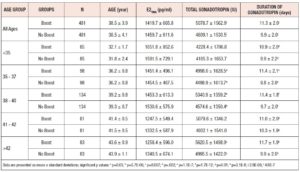

Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table I. There were no statistically significant differences in age or trigger-day estrogen levels between the two groups. As was expected by our preliminary analysis, the Boost group received more gonadotropin over more days of gonadotropin administration than the No Boost group. Administration of a boost increased gonadotropin utilization by one day and resulted in a corresponding increase in the total administered gonadotropin.

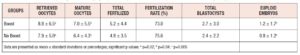

The two groups were compared to assess the effect of a FSH boost on outcomes. The results (Table II) showed small but statistically significant increases in the number of retrieved oocytes, matured oocytes, and euploid embryos formed in the Boost group, as compared to the No Boost group.

Our data further revealed that the boost did not prevent a decrease in estrogen levels following the ovulation trigger; i.e., there were no differences between the Boost and No Boost groups in the number of patients who experienced a drop in their estrogen levels on the day after trigger (14.3% and 11.6% respectively, X2 = 1.5539, p > 0.05).

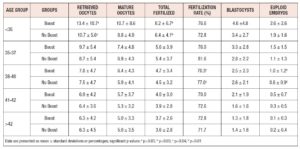

In post hoc analysis, we divided our data according to SART age groups, to determine whether a boost would benefit a particular age group more than others. There were statistically significant differences seen in the number of retrieved oocytes and number fertilized in the <35 age group, as well as in the fertilization rate and number of euploid embryos formed, in the 38-40 age group. However, there were no consistent differences found in the number of retrieved oocytes, number of matured oocytes, number of oocytes fertilized, fertility rate, number of blastocysts formed, or total number of euploid embryos formed for any age group. There were, likewise, no significant differences found for any particular field across all age groups (Table III).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that a gonadotropin boost modestly improves outcomes among patients who achieved similar estradiol levels on the day of trigger. Amongst all age groups combined, there were mild but statistically significant differences in several key outcomes including number of retrieved oocytes, number of matured oocytes, and number of euploid embryos formed. While our post hoc analysis did not demonstrate any significant and consistent improvements within the individual age groups across the various parameters, there was a clear non-significant trend favoring a boost with greater mean values for the number of retrieved oocytes, matured oocytes, euploid embryos, in the boost population. In addition, there remained some significant parameters in the <35 group and 38-40 group. The lack of statistical significance across the other outcomes is likely due both to the smaller population size in these subgroups and the size of the difference in outcomes between the Boost and No Boost patients.

Our study design is unique in the large size of the evaluated population, our usage of randomized matching for comparison of clinically similar patients, as well as in the clinical significance of the outcomes we measured - the number of euploid embryos - which provides valuable insight on the effect of the boost on oocyte development. Previous work on this question analyzed smaller sample sizes, did not utilize PGT-A results in their outcomes, and have yielded conflicting and incomplete results [6-8].

Two recent randomized controlled studies revealed a partial benefit of administering an FSH boost. The first study of 188 women revealed statistically significant improvements in only the rates of oocyte recovery (per mature follicle) and fertilization in a treatment group that received additional FSH at the time of trigger, as compared to the control group. However, there were no differences found in either the number of collected oocytes, the clinical pregnancy rate, or the live birth rate [6]. Nevertheless, the increased rates of oocyte recovery and fertilization with a boost suggests that FSH might play an important part in oocyte maturation and ovulation, and that additional FSH administration might be beneficial to IVF success. Another study that included 109 patients found a statistically significant increase in the number of mature oocytes and embryos formed, in patients who received a FSH boost [7]. However, they too did not find any statistically significant increases in the total number of retrieved oocytes, or in the clinical pregnancy rates, of patients who received a boost. In both these prior studies, a FSH boost was found to provide a benefit to oocyte maturity and embryo development but did not result in any statistically significant improvement in patients’ pregnancy rates.

A more recent double blinded randomized placebo-controlled study analyzed data of 732 women and found no benefit of providing an FSH bolus at the time of ovulation trigger [9]. They found no significant differences in the clinical pregnancy rate, or in the number of retrieved oocytes, embryo quality, fertilization rate, implantation rate, or live birth rate between the two groups of women undergoing GnRH agonist IVF. One limiting factor in this study, however, is that the study population was not tailored to patients who would most likely benefit from a boost - patients with a deficient ovarian response. Finally, a fourth study evaluated a retrospective cohort analysis of 874 IVF cycles and revealed no difference in oocyte maturation, fertilization, or blastocyst formation rates in patients who received an FSH boost, as compared to those who did not [8].

None of these prior studies assessed the effect of an FSH boost on euploidy, a key factor that may elucidate the lack of significance in the clinical pregnancy rate or live birth rate (despite the improvements in fertilization and embryo formation) found in the aforementioned studies. Clearly, then, given the conflicting and incomplete nature of the existing work, there remains some uncertainty as to what effect, if any at all, a trigger-day FSH boost has on IVF outcomes.

Ultimately, our work indicates that a boost portends a modest improvement in patient outcomes, but its benefit is not overwhelming. Judicious use of an FSH boost may be warranted for the right patient and in the right circumstance, and a risk-benefit analysis is warranted with its use. It is also possible, however, that a subset of the population may derive a greater benefit from a boost, but our study was not designed to determine which subset that might be. Although no study, to date, has demonstrated a significant effect on live birth rates in fresh cycles, additional research is needed to determine if there are significant effects of the Boost on live birth rates following transfer of frozen embryos from these cycles.

Adding to the clinical significance of this question, and another important dimension of the debate on the benefits of a boost, are recent discussions in the literature on whether an FSH boost at the time of ovulation induction may be beneficial in mitigating the risk of ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome (OHSS) [10,11]. If confirmed, this might provide an additional reason to administer such a boost in patients at elevated risk of OHSS, even in the absence of significant improvements in oocyte retrieval or embryo development.

Final considerations regarding the design of our study pertain to its retrospective nature and the selection process by which patients were matched into the two groups. By randomly matching patients in both cohorts according to trigger-day estrogen level, we were able to more accurately compare the effect of a boost on clinically similar patient groups. The effectiveness of our randomization process is indicated in the resulting statistically insignificant differences observed in E2trig levels and post-trigger drop of E2 between the two groups. We believe this to be a strength in our study design, when compared to work done previously.

In summary, we evaluated 962 IVF cycles with similar estradiol responses, and compared embryology outcomes in patients who were and were not prescribed supplemental gonadotropin on the day of trigger. The additional dose was associated with small but statistically significant increases in oocyte yield, number of embryos and number of euploid embryos.

Funding: This study was not funded by any outside group or organization.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the NYU Langone Health Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The retrospective analysis was performed under the general protocol i13-00389 approved by the Institutional Review Board of NYU Langone Health.

Authors’ Contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by David McCulloh and Isaac Chamani. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Isaac Chamani and all authors commented on versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: David McCulloh holds management/consultant positions at Granata Bio, Buffalo Infertility and IVF Associates, Biogenetics Corporation, Sperm and Embryo Bank of New York, ReproArt: Georgian American Center for Reproductive Medicine, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Isaac Chamani and Frederick Licciardi have no conflicts of interest to disclose.