Introduction

Evra® (Gedeon Richter Plc., Budapest, Hungary), introduced nearly 20 years ago, was the first transdermal contraceptive patch designed to deliver two hormones. The Evra® patch has high contraceptive efficacy with an overall Pearl Index of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.44–1.35) 1. Studies have shown that the use of the Evra® patch is associated with improved compliance relative to oral contraceptives 2–4. Since its introduction, the Evra® contraceptive patch has been a long-standing option in 60 countries. However, with the evolution of numerous contraceptive options, this patch has become an underused method.

Expanding contraceptive options in the past 2 decades, have allowed women to tailor their contraceptive method to lifestyle and autonomy. However, differences in contraceptive counselling across countries has led to different recommendations 5–7 most likely caused by healthcare provider (HCP) variations, who may be insufficiently informed on all available methods 8 and in differences in the local availability of the various contraceptives. To empower the decisions of users, healthcare providers (HCPs) need to adopt structured counselling, and revisit long standing non-daily methods such as the transdermal patch, Evra®.9–11

In this statement paper, we aim to emphasize the importance of structured counselling and how the transdermal patch can meet an unmet need in contraception when users are sufficiently informed.

Unintended pregnancy rates remain high

Despite the worldwide availability of diverse contraceptive methods, the globally unplanned pregnancy rates remain high. The United Nations Sexual and Reproductive Health Agency (UNFPA) affirmed that nearly half of all pregnancies worldwide (121 million annually) are unintended, having profound consequences for societies, women, and global health. Over 60 percent of these unintended pregnancies end in abortion, almost half of them (45%) performed unsafe, leading to 5 to 13 percent of all maternal deaths 12. Factors contributing to this problem include limited access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, poor education, and poor contraceptive compliance 13. For instance, in Spain, a noncompliance rate of more than 50% to combined hormonal contraceptives has been reported 14. The main reason for noncompliance is forgetfulness, which is especially important with daily methods such as the oral contraceptive (OC) pill, but less for the vaginal ring and the patch. Also limited knowledge about the method and not playing an active role in selecting a contraceptive method are significant factors for non-compliance. 14

Knowledge of HCPs

The awareness and knowledge of HCPs regarding various contraceptive methods influences the consultation process 9,10,15. Various studies show that some healthcare professionals lack adequate knowledge regarding contraceptive options, using outdated information on contraception benefits and risks 9,10. A survey assessing obstetricians and gynaecologists (n=250) from 12 Latin American countries found that knowledge regarding combined oral contraceptive (COC) failure rates and non contraceptive, benefits and risks of COCs was limited 11. Further studies demonstrated that this knowledge gap was more prevalent among older healthcare professionals and family medicine providers compared to younger colleagues and obstetricians and gynaecologists 9.

Knowledge of users

Helping users make an informed contraceptive choice goes beyond supplying a prescription. The chosen method should suit the individual’s needs and counselling should ideally include health benefits beyond contraception 16, like addressing the effect on acne, bleeding profile or hyperandrogenism, and the possibility of scheduling or avoiding bleeding. Providers should also be well informed about extended or continuous use, and should include these in their counselling 17.

A multinational survey evaluating women’s attitudes and preferences, highlighted that many women, including those already using COCs, have limited knowledge about available contraceptive methods and a considerable percentage (53-73%) expressed the desire to learn more about alternative methods 18.

A survey in Sweden 19 examining the knowledge and prevalence of contraceptives among 1016 women (of which 64% were using contraceptives) revealed that for both users and non-users, contraceptive efficacy is of key importance, followed by minimal side effects. Awareness of contraceptive methods varied among current users and only 40.4% were aware of the patch, while 83.6% were aware of COC 19. Awareness of the patch was also low in older women and only 26.7% of current non-users know about the patch.

A study in 1,387 new users in low-income communities in the US, found that contraceptive knowledge in general was low, but initiation of a new form of contraception (i.e. the vaginal ring) was associated with greater knowledge about all methods after seeing the HCP (p < 0.001) 20. Compared to COC and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) initiators, the vaginal ring or patch initiators were more likely to report making their decision together with their provider (p≤ 0.001) and attributed their choice to the HCP’s recommendations (p≤ 0.001) 20.

The importance of counselling

Contraceptive counselling has evolved from a HCP-dominated directive approach towards person-centred structured counselling, focusing on shared decision-making, without potential HCP biases or external constraints 21,22. Counselling focused on trust, respect, and an open dialogue can build an interpersonal relationship, enhancing the overall quality of care and helping to address any concerns or questions the user may have 22,23. Structured counselling may include the use of audio and visual materials with standardized information, provide ample opportunity for questions and engaging women by covering all available contraceptive methods.

If we assume contraceptive counselling includes discussion of preferences and lifestyle, then it should also include quick start 24. Promoting quick start is an interesting option for increasing the use of the chosen contraceptive method 24.

The Contraceptive Counselling (COCO) study, involving 92 gynaecologists, evaluated the effect of a needs-based structured counselling approach on method choice and satisfaction. The research demonstrated an increase in user satisfaction with their current contraceptive method, with a 30% increase in women very satisfied with their method. This included starters, switchers and even women continuing their previous method 25.

Studies have shown that structured counselling is associated with an increased preference for non-daily options such as the patch 26, which has been attributed to the convenience, satisfaction, and self-control of the patch 27. In a Brazilian study 95.3% of the participants were satisfied with the patch compared to their previous method, and users showed an improvement in physical and emotional well-being as well as relief of premenstrual symptoms 28. Notably 99% highlighted the ease of use 28. A focus group study from Mexico reiterated the preference for person-centred counselling instead of mere method effectiveness or a HCP opinion. Establishing trust in the HCP was seen as essential for women's contraceptive needs 29.

In recent years, global family planning programs have increasingly implemented user-centred counselling to empower women, foster decision-making skills, and support reproductive autonomy 30,31. While specific adoption rates of these programs have not been evaluated nor published, it is known that the use of structured counselling in family planning programs and the involvement of healthcare professionals varies across countries. This variation is influenced by factors like the healthcare systems structures, local policies, financial resources, trained HCPs, educational materials, and cultural norms.

Counselling should encompass the entire spectrum of contraceptive care

In many trials assessing the impact of structured contraceptive counselling, uptake of the method has been the primary outcome whereas continued use and effectiveness in pregnancy prevention has been studied as secondary outcomes. Effectiveness is not the sole factor when choosing a contraceptive method and is often given more importance by HCPs. Providing information on non-contraceptive benefits32 and adopting a comprehensive approach to the entire spectrum of care, integrated within the healthcare system, plays a crucial role for reproductive empowerment, ensuring universal access to reproductive healthcare.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the significance of self-care interventions 33 and the importance of offering user-administered contraceptive methods, such as the contraceptive patch, in high-quality family planning services 15,34.

Some countries have appropriately prioritized enhancing contraceptive services. For the promotion of the use of highly effective methods like long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), it is essential to exercise caution 6,35. Overemphasizing these methods could lead to neglecting other critical aspects of access to contraception, limiting the reproductive autonomy and overall quality of contraceptive care 36. It is imperative to recognize factors like the provision of preferred methods, respectful care, and access to discontinuation when desired to ensure women receive individualized contraceptive care.

Counselling and the choice of contraceptive method variations worldwide

Europe

Across Europe well designed non-controlled studies have shown that contraceptive choice can be influenced by structured contraceptive counselling (General Practitioners [GPs], gynaecologists) 5, 27,37–39. These studies were supported by the license holder of a vaginal ring. They included women (aged 15 to 49 years) participating in counselling sessions, specifically addressing the combined hormonal contraceptive pill, patch, and vaginal ring; methods with comparable effectiveness, safety, and tolerability. Counselling involved detailed discussion on effectiveness, mode of action, usage, risks and benefits, and individual suitability. Participants received standardized written information and completed a questionnaire on contraceptive preferences, choices, and the reasons for their decisions, both before and after counselling. The largest of these studies was the European CHOICE study, conducted in Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Slovakia, the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, Israel, Russia and Ukraine38. Results of this study demonstrated that among 18,787 interested users, 47.4% chose a different method than the originally planned. Before counselling, 51.7% chose the pill, 4.7% the patch, and 8.0% the vaginal ring, 9.7% another method, and 25.9% were undecided. After counselling, slightly less women chose the pill (50.8%), while the patch (8.3%) and vaginal ring (29.8%) were chosen more often. Structured counselling significantly reduced (from 25.9% to 4.5%) the percentage of women who initially were undecided. The changes were less pronounced in Northern European countries than in Central and Eastern European countries, where a notable shift was seen to the selection of vaginal ring, with a 28.7% and 36.1% increase in Russia and Ukraine, respectively. This shift to the use of the vaginal ring was influenced by the doctors’ recommendations. Differences in counselling styles (directive versus non-directive) could have impacted the method choice, with Northern Europe focusing more on individual preferences. Recent market introductions may have also influenced counselling and choice. Similar national studies such as an Italian study 7 showed comparable results, with an increased preferences for the vaginal ring and the patch.

Further analysis of the European CHOICE study indicated that women’s choices for the pill, patch or vaginal ring were based on the ease of use, convenience and regular menstrual bleeding 8. The primary reason for choosing the patch or vaginal ring was the non-daily administration. The authors concluded that a method’s perceived ease of use was of greater importance than the perceived efficacy, tolerability, health benefits/risks. Women’s knowledge about a specific method was generally better if they had chosen that particular method 8.

Latin America

In Latin American countries like Brazil, a notable percentage (5.6%) of the population is illiterate 40, equating to 9.6 million people. As a result, providing effective education and counselling can be challenging. Brazilian women appear to have limited knowledge on modern and efficient contraceptive methods, such as LARCs and the patch 41. This lack of knowledge also concerns COCs, which is the most used method in the country 42. The lecture-based approach commonly used among Latin American HCPs, may contribute to the limitations of family planning education. The lectures are exclusively informational, merely covering the technical aspects and rarely consider the participants’ individual needs 43. Brazilian HCPs may not fully recognize the interest of Brazilian women in discussing contraceptive choices 41, and much of the Brazilian population remains unaware of the various contraceptive methods.

In Mexico, Holt et al. conducted a focus group study to determine women’s preferences for contraceptive counselling29. The study demonstrated that user-centred contraceptive counselling is critical to address contraceptive needs and the protection of users’ autonomy. Privacy, confidentiality, informed choice, and respectful treatment were identified as key aspects in counselling. Participants preferred personalised counselling centred on individual needs. Trust in the HCP was viewed essential to meet women's contraceptive needs. This study also highlighted under-represented user perspectives on counselling preferences, which is in line with findings in other studies 44,45. For example, users do not want to feel pressured to adopt a particular method and appreciate receiving comprehensive information about multiple contraceptive methods 45.

Better performance measures are needed to optimize structured counselling.

Current structured contraceptive counselling tools have not been evaluated using validated methods when it comes to satisfaction with structured counselling. This would in fact be valuable research in order to develop better performance measure. Studies evaluating the effect of counselling vary considerably in terms of outcome measures 29, 47. Furthermore, these tools lack robust psychometrical evaluation for reliability and validity across various settings 29,47,48.

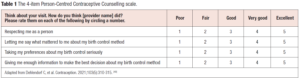

Currently, three scales have been validated. First, the Quality of Contraceptive Counselling (QCC) scale which evaluates three dimensions: information exchange, interpersonal relationship, and disrespect/abuse 29,47 This aligns with the comprehensive QCC framework 48, incorporating counselling and relationship-building elements rooted in health communication and human rights 48. The QCC scale was adapted for specific countries, resulting in a QCC-Mexico, QCC-Ethiopia, and QCC-India. Second, the 11-item Interpersonal Quality of Family Planning (IQFP) which is a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM), primarily designed for research purposes 32. The 11-item IQFP scale was further condensed to a 4-item patient-reported outcome performance measure (PRO-PM) (the Person-Centred Contraceptive Counselling scale, or PCCC) 49 (Table 1). Third, the Person-Centered Family Planning (PCFP) Scale which offers a more comprehensive measure compared to the IQFP and the QCC Scales 50. Unlike the IQFP and QCC Scales, that primarily focus on patient-HCP communication, the PCFP Scale extents its assessments to other crucial aspects of the health facility environment that contribute to patient-centred care. PCFP aims to capture a broader, more holistic understanding of patient-centeredness in the context of family planning services 51.

Revisiting transdermal contraception

Currently only a few contraceptive patches are available; Evra® and Xulane® are similar combined contraceptive patches containing norelgestromin (NGMN) and ethinyl-estradiol (EE), whereas Twirla® is a combined contraceptive patch containing levonorgestrel and EE.

The Evra® patch (Gedeon Richter Plc., Budapest, Hungary), introduced nearly 20 years ago, was the first transdermal contraceptive designed to deliver two hormones. Evra® is a 20 cm2 patch containing 6 mg NGMN and 600 μg EE and releasing 203 μg of NGMN and 33.9 μg of EE per day on the skin 1. Forty-eight hours after single application, steady-state concentrations for NGMN (~0.8 ng/mL) and EE (~50 pg/mL) are reached and further maintained throughout the 7-day recommended wear period 52–54. The licenced regimen consists of one patch applied every week for three weeks followed by one patch-free week. The Evra® patch has a high contraceptive efficacy with an overall Pearl Index of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.44; 1.35) and a method failure Pearl Index of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.31; 1.13) 1. The Ortho Evra® patch that was approved in the US contains a higher dose of EE, with 750 μg EE. The mean steady state concentrations of Ortho Evra® is reached after 2 weeks of application, and ranged from 0.305 –1.53 ng/mL for NGMN and from 11.2 – 137 pg/mL for EE 55. Nonetheless, the higher level of estrogen exposure in Ortho Evra® may be linked to a higher risk of adverse events, as compared to Evra®.

The progestin component of Evra®, NGMN, is a synthetic progestin. NGMN (previously known as 17-deacetylnorgestimate) is the primary active metabolite of norgestimate, a progestin used in many other COCs. NGMN and norgestimate both imitate the physiological impacts of progesterone when interacting with the progesterone receptor. Nevertheless, NGMN has negligible androgenic activity (both directly and indirectly). As a result, NGMN containing compounds may be suitable for women with androgen excess disorders, including hirsutism, acne and lipid disorders.

The side effect profiles of the contraceptive patch and COCs are generally similar with the exception of a higher incidence of breast discomfort and skin irritations. However these side effects tend to subside over time 56.

Data indicate that women prefer contraceptive methods that offer convenience and fit in their daily routines57. In a Canadian study 75% of participants preferred the transdermal contraceptive patch compared to their previous contraceptive method, largely due to the ease of use 58. Treatment satisfaction is vital for long-term continued use and compliance 59. A study in Spain showed that poorly adherent women had significantly lower satisfaction levels with COCs compared to adherent women. This study used a 10-point satisfaction scale, with a mean score of 7.92 for poorly adherent women compared to 8.82 for adherent women. The substantial effect size (Hedges' g = 0.600, p <0.001), indicates a strong relationship between adherence and COC satisfaction 60.

Several studies show that the use of Evra® is associated with high satisfaction and compliance rates when chosen as the preferred contraceptive method 28,61,62. For instance Audet et al. (2002) conducted an open-label trial comparing efficacy, compliance, and treatment satisfaction of the once-weekly transdermal contraceptive patch with OCs. The study involved women (18-45 years) in 65 centres across Europe and South Africa who were randomly assigned to use the registered regimen of the patch or OCs. Both methods were found to be effective, but the transdermal patch reported higher compliance and treatment satisfaction due to its convenient use. The patch also provided good cycle control, improved emotional and physical wellbeing and reduced menstrual symptoms compared to OCs. There were no significant differences in sexual function 56,63. Interestingly, unlike with OCs, treatment satisfaction with the patch increased with age, potentially due its convenience as responsibilities accumulate with age 64.

In a similar study conducted in Brazil 28, satisfaction was assessed in participants using the transdermal contraceptive patch, relative to their previous contraceptive. After 6 cycles, 95.3% of the participants were more satisfied with the use of the patch compared to the previous method 28. At the end of the study, 59.5% of women reported physical well-being improvement, 58.0% reported better emotional wellbeing and 63.2% of women reported less premenstrual symptoms. The use of spare patches, to apply in case of detachment, decreased over time indicating that continued use improved patch application 28,65.

A more recent study involving 778 women across eight European countries reported similar findings 61. Previous oral contraception users were satisfied with their previous method, but compliance was poor with 77.8% reporting missed pills. After 3 and 6 cycles, over 80% of participants expressed satisfaction with the patch. At the end of the study 74% preferred the patch over their previous method. Nearly 90.5% of cycles were completed with perfect compliance. The authors suggested that transdermal contraception offers a valuable contraceptive option with high compliance and efficacy 58.

Contraindications must always be considered before recommending any combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs), including Evra®. The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with contraceptive patch use equates approximately 6 to 12 VTE cases per year out of 10,000 women using the patch 1; in case of COCs with levonorgestrel, norethisterone or norgestimate the incidence is 5 to 7 VTE cases per year out of 10,000 users. Nonetheless, the VTE rate with patch use is lower than in pregnant women or during the postpartum period 1.

Recommendations

Many women tend to associate contraception with the oral contraceptive pill and may not be fully aware of other contraceptive options. Structured counselling aims to prioritize the need of users over the HCP’s influence. The HCPs role is to offer structured contraceptive counselling, using standardized formats like videos or information forms and allowing time for questioning. While traditionally the pill was the most commonly used contraceptive method, structured counselling, like in the CHOICE study, has shown to lead to a shift in preferences, with more women choosing non-daily options such as the vaginal ring and patch 38. Providers must keep in mind that users prefer convenience over efficacy. Transdermal contraception should be part of contraceptive counselling so as to sufficiently inform users on all contraceptive options.

Transdermal contraception has many advantages such as the constant and prolonged release of hormones, maintaining constant therapeutically effective concentrations, avoiding degradation of active substances and difficulties in absorption during gastrointestinal tract transit, the ease of once-weekly application and the higher patient compliance rate when compared to oral contraception. Unlike long-term or injectable methods, the contraceptive patch does not require administration by a healthcare professional and can be easily reversed, promoting self-care. Furthermore, relative to the vaginal ring, the ease of application of the patch avoids vaginal insertion and thereby may be suitable for users who find tampon use difficult. Non-contraceptive benefits of transdermal contraception are the same as those for other CHCs, including reduced acne, prevention of dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndromes as well as reduction of withdrawal bleeding 66. Furthermore, transdermal contraception may offer advantages for specific groups, such as women with poor compliance to OC and women seeking an alternative to daily administration, particularly those with an irregular lifestyle such as frequent travellers. Also, for first time users, who are likely to be less compliant, the non-daily patch may provide a good contraceptive option 14.

Numerous studies have shown high user satisfaction with transdermal contraception, whereby users preferred this form of family planning over their previous method 61. This makes transdermal contraception a valuable addition to contraceptive options with the potential to offer high compliance and efficacy 61. Moreover the concept of a patch as a method for pharmaceutical delivery has proven to be very effective14, and is widely used in post-menopausal hormone treatment 67.

Conclusion

Structured contraceptive counselling enhances shared decision-making and reduces HCP bias. Geographic differences in contraceptive recommendations exist. These are not due to women being inherently different in different geographical areas. Instead, these differences are caused by HCP variations in counselling and differences in the local availability of the various forms of contraception. Empowering users requires structured counselling by HCPs for informed decision making. Ultimately, users are more satisfied with their contraceptive method when they are sufficiently informed which also increases adherence and subsequently effectiveness. Effective contraceptive service counselling strongly relies on client-HCP communication, encompassing information exchanged and interpersonal relationship.

Studies show that structured counselling boosts the interest in the less common, non-daily and non-oral forms of contraception, which is attributed to the convenience, satisfaction, and self-control of these methods. Comprehensive contraceptive counselling should therefore also include the innovative and simpler-to-use contraceptive methods like the patch and vaginal ring, without HCP assumptions, while taking into account any contraindications.

Acknowledgements

Silvia Paz, Nazanin Hakimzadeh, and Mireille Gerrits (Terminal 4 Communications, Hilversum, the Netherlands) provided Medical Writing support.

Conflicts of interest

KGD reports ad hoc lectures or providing expert advice for RemovAid, Organon/ MSD, Bayer AG, Gedeon Richter, Exeltis, Natural Cycles, Mithra, MedinCell, Cirqle, Norgene, Exelgyn, and Myovant, outside the submitted work. HKK declares honorariums for lectures from: Abbvie, Actavis, Bayer, Gedeon Richter Exeltis, Nordic Pharma, Natural Cycles, Mithra, Teva, Merck, Organon, Ferring, Consilient Health and providing expert opinion for Bayer, Evolan, Gedeon Richter, Exeltis, Merck, Teva, TV4 och Natural Cycles, Pharmiva, Dynamic Code, Ellen, Estercare, Pharmiva, Gedea, Gesynta, Essity and Preglife. HKK is investigator in trials sponsored by Bayer, MSD, Mithra, Ethicon, Azanta/Norgine, Gedeon Richter, Gedea, planned study for Organon, Pharmiva and Takeda. MF has disclosed speaker honoraria from Gedeon Richter. MAO has received speaker fees and participated in medical advisory boards for Gedeon Richter, Theramex and MSD. JL and CAP have no conflicts of interest.