Introduction

The availability of modern methods of contraception has been described as the “first reproductive revolution” in the history of humanity. Indeed, the availability and widespread use of modern contraceptive modalities represents more than a technical advance: it constitutes a true “social revolution” that greatly contributed to changing the future of the human race [1]. It is for this reason that when speaking about contraception we should not limit ourselves to discussing technology: old versus new methods; short-acting versus long-acting methods; reversible versus irreversible methods. We must also concentrate on the profound changes that it caused in the meaning of human sexuality of which humanity has not yet come to terms [2].

Here we will attempt to briefly describe the global view necessary to understand both the technical and social aspects of a widespread use of modern methods of fertility regulation. In doing so, it is necessary to start from the first objective for promoting contraception: control of the population explosion that characterized the XX century. However, its utilization has been uneven, with countries where more than 60% of eligible persons avail themselves of this tool and countries where utilization is below 25%. Mention must also be made of the fact that, at the global level, contraception has been an unequalled tool to decrease the need to recur to an abortion, especially for the termination of pregnancies carried out under unsafe conditions.

There is also an invaluable positive effect that contraception had in the battle for women’s empowerment, allowing them to decide if, when and how many children to have. Last, but not least, mention will be made of the role of contraception in improving the health of women. This is a neglected area since the emphasis has always been on the negative effects of the various methods.

Contraception and population control

During the second half of the XX century the newly developed contraceptive methods have been utilized as the best available means to quench the population explosion. Fear of overpopulation is certainly not a new feature; advocates of population control have existed for centuries. In the VII/VIII century, the Syrian Bishop Saint John Damascene proclaimed: ‘The world is now congested and can no longer contain us’ [3]. However, a real movement against overpopulation arose only some 200 years ago and it was only in the second half of the XX century that the idea of a need to halt population growth become popular at the governments’ level.

According to an essay published in 2009 by RV Short [4], the first to attempt the study of the effects of population growth was Scottish economist, Adam Smith who, pioneering the development of a Global Economy, in 1776 issued a prophetic warning in his book The Wealth of Nations. He identified a fatal flaw in the Economy, namely that it is a human artefact that gives unlimited power to our Selfish Genes, with no negative feedback controls. Such an economic philosophy of greed will ultimately run counter to the inherent ecological constraints of the planet.

In 1798, the Rev. Thomas Robert Malthus anonymously published an “Essay on the Principle of Population” [5] in which he stated that the impact of population growth is far greater than the earth's ability to produce livelihoods for humanity, because the population, if not controlled, grows with a geometric ratio, while the means of subsistence increase arithmetically. Interestingly, Malthus condemned abortion an "improper art that hides the consequences of irregular relationships", as well as contraception which for him amounted to "promiscuous concubinage”.

Malthus, described the following factors as capable of influencing the growth of population:

- A “preventive check”: late marriage.

- A “positive check”: high levels of infant and childhood mortality.

- A second “positive check”: wars, infanticide, plague, and famine.

At the time when Malthus launched his alarm, world population was estimated at between 900 million and one billion and its dizzying growth did not begin until 150 years later. The international community did not accept the reality of overpopulation until the end of the sixties of the XX century, and not without disputes, disagreements, and sharp contrasts. When, in 1951, the Indian Government asked the World Health Organization (WHO) for help in introducing the so-called "Rhythm" method of family planning, the general climate was radically different from today's and completely hostile, to the point that the mere possibility of the WHO's participation in the 1st World Population Conference in 1953 resulted in threats from some Member States to leave the Organization [6].

Slowly, the need for a control of human growth was accepted by the major religions of the world, including the Roman Catholic Church with the following statement made on 19 January 2015 by Pope Francis: «Good Roman Catholics do not need to breed like "rabbits", but should practice "responsible" parenting instead» [7].

Until recently there have been persons who believed that «Overpopulation is not the problem» These people reject the idea that ‘like bacteria in a petri dish, our exploding numbers are reaching the limits of a finite planet’. They argue that at the basis of the 'defeatist' philosophy there is a profound misunderstanding of the ecology of human systems because the conditions that sustain humanity are not natural, nor have they ever been. Since prehistoric times, men have used technology to support population growth, each time exceeding the capacity of the natural ecosystem [8]. At any rate, suddenly in the nineteen sixties everything changed, and the alarm sounded: «Population growth is drowning the planet. Famines, Poverty, Underdevelopment, Environmental degradation kill the planet».

The years that followed were difficult: family-planning was promoted almost everywhere, with many governments attempting to use contraception and even abortion to slow, or altogether stop population growth. In 1980, China imposed to its couples to have only one child and strictly enforced it with punishments including fines and often forced abortions [9]. During the period in which Indira Gandhi assumed emergency powers (1975-1977), she advocated widespread use of sterilization and an astonishing number of 6.2 million of mostly poor person sterilizations were carried out in just a year [10].

The situation however, changed in the last decade of the XX century with more and more countries leaving in the hands of individual couples the decision on whether and how many children they wished to have. This led to the present paradox: all European Union countries are below ‘replacement level’ (2.1 children per family), with 1.53 live births per woman in 2021 (ranging from 1.13 in Malta to 1.84 in France) [11], whereas in the majority of African countries there often families with 5 or 6 children with a mean in 2023 of 4.155 births per woman [12].

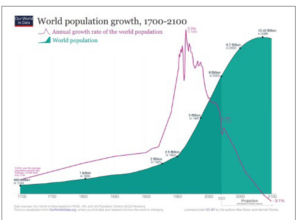

In conclusion, as shown in Figure 1, the demographic explosion has been a unique phenomenon of the XX century with a peak growth rate around 1950, and a prediction that the global population will begin to decrease by the year 2110.

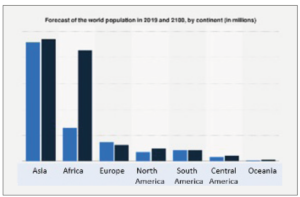

At the same time, as shown in Figure 2, there remain severe inequalities in population growth; these will have major consequences especially for the Industrialized World.

The utilization of contraceptives in the various areas of the world

Differences in population growth are reflected in differences in contraceptive utilization. Figure 3 shows the global contraceptive situation as per 2019. It has been calculated that some 10% of people who wished to utilize a modern method did not have access to it, whereas 44% utilized a modern method and 10% relied on a traditional method. Finally, 42% had no need for a contraceptive.

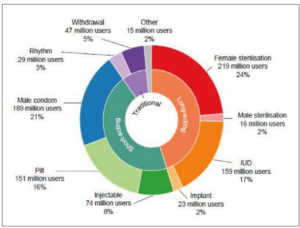

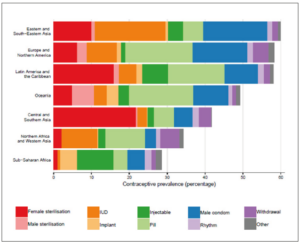

The global distribution of the utilization of methods is summarized in Figure 4.

With a total of 26%, the most widely used method was sterilization (mostly female), followed by the male condom (21%) and intra-uterine devices (mostly copper or levonorgestrel releasing systems) (17%). Oral contraception accounted for 16% of the total, followed by injectables (8%), withdrawal (5%) and the rhythm method (3%).

The proportion of users varied widely between geographical areas, with the highest utilization in Eastern and South-eastern Asia, followed by Europe and North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean, all around 60%. In Oceania the percentage was a little over 50%; in Southern Asia the rate fell to around 45%, and in Africa was around 40% in North and Western countries and below 30% in Sub-Saharan nations (Figure 5).

Contraception to decrease the need for an abortion

The Guttmacher Institute calculated that roughly 121 million unintended pregnancies occurred each year between 2015 and 2019; of these unintended pregnancies, 61% ended in an abortion with a total of approximately 73 million per year [13]. Contraception is a powerful tool to decrease the need to recur to a pregnancy termination if good continuation is ensured but, to achieve this, potential users must be able to choose among methods and feel at ease with their choice.

It must be stressed that ethical considerations influence the choice of strategies aimed at decreasing the need to terminate a pregnancy, especially the possibility to recur to emergency contraception. In this regard, a recent perspective article [14] after summarizing the documented presence of a massive, early-preimplantation embryonic loss, proposed to make a clear distinction between the first days and the subsequent 9 months of gestation: “on the one hand, the word gestation should be employed to define the period from fertilization (whether in vitro or in utero) to birth; on the other hand, the word pregnancy should be used when referring to the period after implantation has been completed”. Accepting this distinction would eliminate any doubt that emergency contraception may terminate a pregnancy.

Of particular importance is the role of contraception in teenagers. Some thirty years ago, Dreyfuss [15] pointed out that in a proportion of 13 to 30% in western countries and 3% in East Asia or in Northwest Africa, abortions were a reflection of early sexual activity without contraception; for this reason he stressed the major role that contraception can play especially for teenagers who are at an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, pre-eclampsia, anemia, hemorrhage, and prematurity, as well as social difficulties. Hence, while access to contraception is important for all women, it is vital for teenagers, in order to avoid such prejudicial situations. In fact, data from several industrialized countries indicate that, where contraception is well established, utilized by the vast majority of people and it is associated with a proper sex education, the need to resort to an abortion is substantially decreased [16].

According to Marston and Cleland [17], a rise in contraceptive utilization is correlated to a reduction in abortion rates in countries where levels of fertility are constant, while where fertility rates fall, the increased contraceptive use is unable alone to meet the need for fertility regulation and abortion rates increase. When fertility rates become constant, contraceptive use continues to increase while abortion rates fall.

Today’s reality is characterized by two contrasting situations: on the one hand, liberal abortion legislations prevail in Industrialized Countries; on the other, restrictive laws are still the norm in the majority of low- and middle-income countries. Ishola et al. [18] recently carried out a systematic review to determine the effects of abortion law reforms in Uruguay, Ethiopia, Mexico, Nepal, Chile, Romania, India, and Ghana. They concluded that liberalization of pregnancy termination was associated with a reduction in fertility, especially among younger women from 20 to 34 years of age, as well as lower maternal mortality. In this connection, access to safe abortion (i.e., carrying the procedure under conditions that minimize their risk) has become a globally contested policy and social justice issue, because it conflicts with religious and moral norms, producing the seemingly endless debate opposing the right to life and personhood of a fetus to the rights of women to decide about their own bodies. The truth is that a number of Developing Nations have agreed to address the health consequences of unsafe abortion, though they stopped short of committing to providing comprehensive services [19].

One last consideration relates to the negative effects of the so-called “pill-scares”, the widespread publicity given to reports of major adverse effects of combined oral contraceptives (COC), that invariably proved not to be true. As an example, the impact - locally and internationally - of the action taken by the U.K. Committee on Safety of Medicines at the end of 1995 of recommending a switch from third generation oral contraceptives to older agents, was severe. The British Birth Control Trust calculated that some 3,000 extra abortions took place because of the sudden abandonment of contraception by women worried about their health [20]. Although the Irish Medicines Board did not recommend such a switch, Williams et al. [21] observed a marked fall in the overall use of the COC in Ireland, a trend that was similar to that noted in the U.K.

Contraception as a tool for women’s empowerment

We have alluded to the coercive nature of policies adopted by some countries in the seventies and eighties of the XX century. These excesses created a global movement opposing forced family planning and led to the major changes brought about by the International Conference of Population and Development held in Cairo, Egypt on 5-13 September 1994 [22].

Among other achievements, the Conference approved a Program of Action that contained the definition of a new public health entity: “Reproductive health” that, as defined by WHO, “Is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes. Reproductive health implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so” [23]. As it can easily be understood, this represented a 180 degrees difference from the prior national programmes that were often oblivious of the needs and wishes of induvial couples.

The following year, another world Conference, the Fourth World Conference on Women, was held in Beijing, China, from 4 to 15 September 1995 [24], under the banner “Action for Equality, Development and Peace”, further promoted an agenda for women’s empowerment that is now considered the key global policy document on gender equality. Widespread use of contraception was again of paramount importance in promoting women’s empowerment and in Beijing women became active and equal partners in the solution of the world’s problems. Three decades later, contraception still represents an important tool in the struggle to achieve the empowerment of women and in ensuring that they enjoy rights equal to those granted to men. In this respect, the history of the progression of women towards equality with men is clearly paralleled by the history of the evolution of the meaning of sexuality, with contraception becoming a major factor in this evolution. Effective family-planning had a major impact also on the lives of individual couples and especially of women; it was a major tool to achieve equality between the two sexes. Progress has definitely been made, but much still needs to be done as shown in countries such as Afghanistan and Iran.

Contraception to improve health

The already mentioned occurrence of several consecutive “pill scares” has focused attention to a fundamental issue in contraception, namely its proper utilization: knowing the contraindications to each method is a major step in improving health. In this connection the WHO took a leadership role in publishing a detailed evaluation of Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. The first edition was published in 1995 and the fifth in 2015 [25]; it contains first a description of the methods and of their various levels of contraindications; the second is dedicated on explaining how to use them. As it would be expected, the recommendations enumerated are based on the latest epidemiological and clinical information.

In discussing health consequences of using the various contraceptive modalities one cannot help but to notice that for decades the emphasis has been on the side effects and even dangers, mostly of hormonal contraception; only relatively recently their positive actions have been clearly stated. As an example, whereas for years The Lancet published articles mentioning a number of negative consequences of COC, its cover on 26 January 2008, stated: “Oral contraceptives have already prevented some 200,000 ovarian cancers and 100,000 deaths from ovarian cancer, and over the next few decades the number of cancers prevented will rise to at least 30,000 per year” [26]. That issue contained a major report on a reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies involving 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls [27].

Today, the public seems to have acquired confidence in the various contraceptive methods, although the situation remains complex because of the sensationalism of the media. A few years ago, Lackie and Fairchild [28] observed that both the scientific and media communities have been active in the discussion, debate, and delivery of information about risk of contraceptive use. They stressed the dramatic consequences of the “pill scares”, that were both good and bad: on the one hand, it helped to change dosages and norms regarding the public's right to know and assess dangers; on the other, it caused periodic increases of unplanned pregnancy and abortion rates.

Although non-contraceptive benefits of contraception were identified and described already half a century ago [29], it has been argued that they represent a “well-guarded secret”. Indeed, for decades the emphasis has been on risks associated with the use of the ‘pill’, with several successive “pill scares”, whereas mention of the benefits associated with its use have been neglected, to say the least.

Today the situation has substantially improved, with a number of informative reviews published in the last decade [30-33].

Contraception as a preventive and treatment tool for gynecological conditions

Besides improving health there is another important and not sufficiently known utilization of hormonal contraception: its use in the prevention and treatment of a number of pathological conditions and diseases.

Using the words of Schrager et al. [33], “contraceptives that contain estrogen and/or progestins are used by millions of women around the world to prevent pregnancy. Owing to their unique physiological mechanism of action, many of these medications can also be used to prevent cancer and treat multiple general medical conditions that are common in women”. Among these, worth of mention are their capacity to prevent ovarian, uterine and colon cancer, and be used to treat women with a variety of gynecological and non-gynecological conditions, such as uterine fibroids, heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and its often-associated hyperandrogenism, and premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

A detailed description of the many therapeutic applications of hormonal contraceptives is beyond the scope of this review. Therefore, here they will be briefly mentioned.

With regard to cancer prevention, there is an abundance of information on the protective effect of COC on ovarian cancer. As an example, a very large Danish prospective, nationwide cohort study found that, compared with never users, a substantial decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer occurred with current, recent, and former use of any type of hormonal contraception. In addition, relative risks among current or recent users decreases with increasing duration from 0.82 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.59 to 1.12] with ≤ 1-year use to 0.26 [95% CI: 0.16 to 0.43] with >10 years of use [34]. A similar situation exists for endometrial cancer. Indeed, another very large Danish prospective, nationwide cohort study found a lowering of the risk of endometrial cancer in current and recent users of any hormonal contraception: 0.65 (95% CI: 0.52 to 0.83); and 0.57 (95% CI: 0.43 to 0.75) for combined contraceptives. An exception is progestin-only contraceptives, including the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) for which no significant effect was found. The positive effect increased progressively with duration of use and continued for >10 years after stopping the COC [35]. Finally, a population-based case-control trial found an inverse association between colorectal cancer and use of COC or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) [Odd ratio (OR) = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.64 to 0.87], or both [OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.48 to 0.70] [36].

A decreased risk of developing fibroids seems associated with current use of progestin-only injectables, although no consistent patterns were observed for other forms of hormonal contraception [37]. In a multicenter, randomized controlled, noninferiority trial in the Netherlands, women with HMB were randomly allocated to treatment with either the LNG-IUS, or endometrial ablation. Investigators concluded that, although the LNG-IUS decreased heavy bleeding in a significant way, difference existed in favor of endometrial ablation [38]. A Cochrane review concluded that there is moderate-quality evidence suggesting that the use of COC over six months reduces HMB in women with serious bleeding from 12% to 77% (compared to 3% in women taking placebo). However, COC was less effective than the LNG-IUS [39]. A very recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials in patients with PCOS compared the use of COC versus no medical treatment and concluded that there was a benefit in terms of cycle regulation, but its utilization as frontline medical treatment is still based on established efficacy in the broader general population [40]. Finally, a Cochrane review of the use of COC containing drospirenone and ethinylestradiol versus placebo, concluded that the combination may improve overall premenstrual symptoms (standardized mean difference: -0.41, 95% CI: -0.59 to -0.24) [41].

Conclusion

As shown in Figure 6, in its relatively short existence modern contraception went through several stages. It started as a series of methods to avoid unwanted or untimed pregnancies and to quench the population explosion of the second half of the XX century, then it became a powerful instrument of a social revolution, giving women a tool to achieve gender equality.

Finally, over time contraception began to be employed to improve health by preventing certain diseases, first and foremost gynecologic cancers. Today, hormonal contraception in its various forms has become an important therapeutic tool for a number of diseases.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare having no conflicts of interest.