Introduction

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (SLCTs) are rare, accounting for less than 0.5% of ovarian neoplasms; moderately and poorly differentiated forms are the most common. They can occur at any age, but are usually found more frequently in women aged between 20 and 30 years [1].

Between 40% and 60% of patients are virilized, while occasional patients have estrogenic manifestations. Clinically, there is defeminization characterized by amenorrhea, atrophy of the breasts, and loss of subcutaneous fatty deposits, which is often the first expression of the disease. This is followed by signs of masculinization, such as clitoral hypertrophy, and voice deepening. Usually, the female characteristics return after excision of the tumor, but the manifestations of masculinization disappear slowly [2].

A solid or mixed (solid and cystic) mass may be identified on ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Over 97% of SLCTs are unilateral [3]. They range in size from 2 to 35 cm (mean 12–14 cm).

The overall prognosis of SLCTs is favorable, but the prognosis correlates with tumor grade and histological subtype. Patients with well differentiated tumors have close to 100% survival. Moderately differentiated tumors display malignant behavior in 10% of cases, while poorly differentiated ones do so in 13–59% [4]. The malignancy rate is low; malignancy manifests as pelvic and abdominal dissemination, and not as distant metastases [5]. Heterologous elements, a retiform pattern, tumor rupture and spread outside the ovary (stage II or higher tumor stage) are adverse prognostic factors.

Case

An 18-year-old female presented to the Section of Gynecological Endocrinology of our hospital in December 2018, referred by a private doctor for evaluation of presenting signs of virilization with secondary amenorrhea for two years.

Personal history:

Menarche at the age of 13, regular menstrual cycles until 2016. No sexual debut. Last menstrual period reported in September 2016, with deepening of the voice since then.

Physical examination:

Height: 1.60 m. Weight: 50.700 kg. BMI: 19.8. Waist circumference: 73 cm. Normal blood pressure. Acne on face, chest, abdomen and buttocks; hair on face, back, chest and abdomen. Breast atrophy (the patient reported a decrease of two bra sizes). Clitoromegaly of approximately 4 cm. The patient reported an increase in her body hair since she was 10 years old (Figure 1).

Investigations performed:

- Gynecological US: Uterus in anteversion and anteflexion and measuring 54x39x52 mm, endometrial thickness 5.6 mm, right ovary measuring 24x27x26 mm with a volume of 9.5 cm3, left ovary measuring 56x34x51 mm with a volume of 51 cm3. No microfollicles visible.

- Laboratory:

a) Luteinizing hormone (LH) 2.9IU/l

b) Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) <1IU/l

c) Estradiol 34 pg/ml

d) Testosterone 7.65 ng/ml

e) Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) 3290 ng/ml

f) Cortisol 16.6 ng/ml

g) D4-Androstenedione (D4A) 4.6 ng/ml

Blood tests for ovarian tumor markers including beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, Ca 125, Ca 19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha-fetoprotein were normal.

- MRI with gadolinium contrast was not performed due to patient’s intolerance.

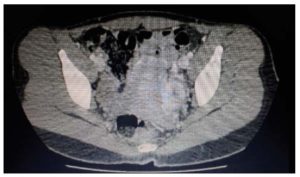

- CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast: liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys and both adrenal glands were unremarkable. Left ovarian enlargement due to multilobar formation of soft tissue density containing some areas of liquid density, with a global measurement of 4.5x3.2 cm, compatible with a solid lesion. Absence of free liquid. No images compatible with peritoneal implants were observed (Figure 2).

In view of the raised serum testosterone level and pelvic CT findings, the initial impression was an androgen-producing tumor of ovarian origin.

Laparoscopic surgical removal of the tumor lesion was proposed, which was performed on March 22, 2019. Intraoperative findings included a regularly enlarged left ovary; the other intrapelvic organs were preserved. Laparoscopic lumpectomy was performed with preservation of the remaining ovarian tissue. A sample of peritoneal fluid was taken. The patient’s progress was good and she was discharged on the 3rd postoperative day.

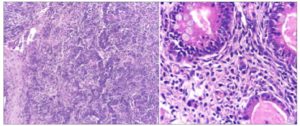

Histology confirmed the diagnosis of a moderately differentiated SLCT with heterologous elements. The abdominal fluid cytology was negative (Figure 3).

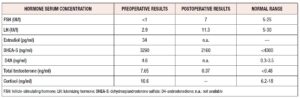

The first follow-up lab tests a week after surgery gave the following results (Table 1):

- - LH 11.3IU/l

- - FSH 7IU/l

- - Total testosterone 0.37 ng/ml

- - DHEA-S 2160 ng/ml

- - Estradiol and D4A: no reagents available.

The patient reported spontaneous menstruation 27 days after surgery, an improvement in voice and hair alterations with a decrease in depilatory frequency (from twice a day to once a week). She continued with outpatient monitoring. Her testosterone levels normalized. Clinically, there appears to have been a decrease in her body hair. At the 3- and 6-month follow ups, the patient’s progress was good, with no evidence of metastasis or recurrent disease (Figure 4).

Discussion

SLCT is a rare sex cord-stromal tumor that accounts for approximately 0.5% of all ovarian neoplasms. Its histology varies depending on the grade, and it is composed of sex cord cells (Sertoli cells) and stromal cells (Leydig cells).

Almost all cases are unilateral (97%) and generally confined to the ovary at diagnosis [3].

This tumor can appear at any age, being more frequent in women aged 20-30 years [2]. Our patient was 18 years old. The SLCT or androblastoma is characterized by the production of androgens, so the clinical manifestations are, in 40-60 % of cases, symptoms and signs of virilization, such as a hoarse voice, abnormal hair distribution, hirsutism, clitoromegaly, menstrual abnormalities, chronic anovulation and infertility, all associated with abnormal laboratory tests, such as elevated plasma testosterone (at least 2.5 times its normal value) [5,6]. In the reported case, strong signs of virilization (increased body hair with male distribution, clitoromegaly) were found. Our patient presented with rapid signs of virilization and secondary amenorrhea of 2 years’ duration. Her initial laboratory tests showed total testosterone levels in tumor ranges. For this reason, we immediately ordered imaging studies to test for adrenal or ovarian tumor production and ruled out other causes of hyperandrogenism, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, Cushing’s disease, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and so on.

SLCT has a non-specific appearance. On US, this tumor usually presents either as a distinct hypoechoic mass or a heterogeneous mass that is primarily solid with multiple cystic spaces. Small virilizing SLCTs may be easily detected using color Doppler US rather than transvaginal US alone. On CT images, a soft-tissue attenuating adnexal mass is usually seen. The solid tumor portions characteristically exhibit avid contrast uptake. Our patient's US failed to detect the presence of an ovarian mass, which was only identified by CT of the pelvis.

The prognosis of SLCT is good. The most important prognostic factors are the stage and degree of histologic differentiation [2,7]. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease is confined to the ovary (stage I) and, therefore, conservative management is possible [8-11].

In our patient, surgery was rapidly performed by the gynecology team, confirming the presence of a tumor confined to the left ovary (stage I); therefore, the tumor was removed. After surgery, testosterone levels returned to normal with a concurrent improvement in clinical hyperandrogenism.

This is a classic example of defeminization in a young woman caused by an androgen-producing tumor. Although the patient’s condition is constantly improving (appropriate menstrual cycles, a decrease in depilatory frequency, restoration of breast size, and partial regression of clitoromegaly), as the pathologic examination revealed a moderately differentiated tumor, it is imperative to monitor her for recurrence. Therefore, a follow-up of her clinical condition (by assessing menstrual cycle regularity) and of her hormonal laboratory tests (by monitoring testosterone levels) will be crucial.

Conclusion

The SLCT is a very rare entity among ovarian tumors that should be suspected in young patients with a history of menstrual irregularity and signs of virilization. Fortunately, most cases present with disease confined to the ovary at the time of diagnosis, making conservative management possible with a view to preserving future fertility.

It would be interesting to assess whether the hyperandrogenic environment in this patient over the last two years will be followed by normal ovarian behavior or instead result in the development of clinical symptoms suggestive of polycystic ovary syndrome. For such an assessment, a long-term clinical and biochemical follow-up is required.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Patricia Lembo for referring the patient.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.